Posted 1st September 2008 | No Comments

The ‘bad news’ report that helped build today’s railway

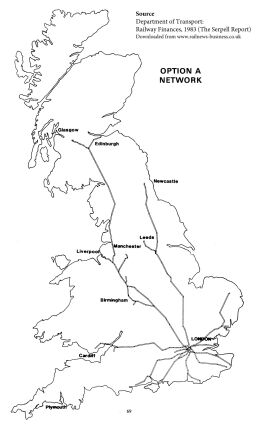

Serpell’s Option A

(Revised with minor amendments and addition of distances in kilometres, June 2024.)

When the Serpell report was published in 1983 it sent shockwaves through the railway industry.

Its most extreme option suggested that a network consisting of just 1630 miles [2623km] was the largest that would be viable without subsidy.

The report set out options but made no firm recommendations, unlike the Beeching report of 1963. In any case, it was never acted upon.

The rejection of Serpell helped to trigger a degree of modernisation, although the British Railways Board's plans for widespread extensions of electrification were not funded, with the result that electrification only proceeded on a few routes, while the Advanced Passenger Train project was terminated. Even so, one effect of Serpell was to modify official attitudes, after ministers realised that the more extreme options in the report went too far to be publicly acceptable.

In this special report Alan Marshall digs into the files to relate a critical time in railway history.

It may seem strange to younger readers – and at a time when there is growing concern about capacity – that in 1983 rail managers were fighting off proposals that could have seen the network slashed to only 1630 miles, or 2623km.

This was an option put forward by a committee of inquiry set up by Margaret Thatcher’s government and chaired by Sir David Serpell, a retired senior civil servant appointed to the British Railways Board.

Sir David, who has died recently aged 96, was aggrieved by reaction to his report in 1983 because its concern with railway finances was ‘in accordance with our terms of reference’.

The committee said: ‘Reductions in the size of the network will be required if the level of financial support for the railway is to be lowered substantially.’ (page 85 of the Serpell Report)

A network of only 1,630 miles was the largest Serpell’s committee considered would be viable without subsidy. Even then, it would have made a profit only because of freight traffic.

Because it was labelled Option A, it became the one that attracted the attention of many politicians and journalists.

Option A (page 69 of the Serpell Report) included no railways west of Bristol in Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, almost no lines in Wales and nothing north of the Scottish central belt. In East Anglia only the main line to Ipswich and Norwich would have survived. Even the East Coast Main Line north of Newcastle was removed, while Leeds was effectively left at the end of a branch line.

Worse still, one member of the committee – known to be close to Prime Minister Thatcher’s personal economics adviser – produced his own report, causing confusion and heightening anxieties about the rail system’s future.

Debate

Serpell’s committee followed years of debate between BR and the Government.

Attitudes to the railways had hardened following Margaret Thatcher’s election and the appointment of Alan Walters, a champion of monetarism, as her economics adviser.

The early years of Thatcher’s governments were marked by a serious economic recession that caused a big decline in BR’s finances. The situation was made worse by a major steel strike and then by disputes in the rail industry itself – culminating in a two-week virtual shutdown in July 1982, when most ASLEF drivers went on strike against ‘flexible rostering’.

That dispute alone cost BR £150 million – equal to £400 million in 2008 prices.

BR was working under a directive to maintain the rail system at its 1974 size, but government funding was considered inadequate and BR warned that routes at the fringes of the network faced closure because there was insufficient cash to maintain them safely.

In one of his most memorable phrases, BR’s chairman Sir Peter Parker – referring to outstanding track renewals of 800 miles [1287km] and 300 miles [483km] of speed restrictions – described the crisis as ‘the crumbling edge of quality’.

Efficiencies

Meanwhile, the Government felt BR should achieve greater efficiencies, although a study by Leeds University had already demonstrated that BR was the second most cost-efficient railway in Europe, after Sweden.

BR was also trying to revive the Channel Tunnel and pressing for a substantial rolling programme of mainline electrification, based on a three-year joint review with the Department of Transport.

But in 1982 BR could not even get government approval for just 27 miles [43km] of electrification on the East Coast Main Line from Hitchin to Huntingdon, let alone as far as Leeds, Newcastle and Edinburgh.

Review

Against this tense background, government and BR agreed there should be a thorough review. But how – and who should do it?

BR wanted a joint review, similar to the electrification study. But the Conservatives were against BR involvement – not least because of hostility to Sir Peter Parker, who had stood as a Labour parliamentary candidate in the 1950s.

Many leaders of blue chip companies such as Unilever, ICI and Bass were reportedly approached, but all turned it down.

Eventually, Sir Peter Parker proposed that Sir David Serpell, a member of the BR Board since 1974, should lead the inquiry. Serpell had eminent credentials, having retired as Permanent Secretary at the Department of the Environment and, as a younger official, had claimed to have persuaded Dr Richard Beeching to become chairman of the British Transport Commission in 1961.

Serpell resigned from his BR position to head the committee but arguments continued about membership. Accountants Peat Marwick Mitchell had been appointed to audit BR’s budget, so senior partner Jim Butler was chosen.

Other members then selected were Leslie Bond, a Rank Organisation director and former Trusthouse Forte managing director, and Alfred Goldstein, senior partner of consulting engineers R. Travers Morgan.

Concerns

Goldstein’s appointment raised wider concerns about the government’s motives, as he was a close friend of Alan Walters and favoured converting railways into roads.

The Butler and Goldstein appointments also provoked heavy criticism because their consultancies were awarded work worth £627,000 (£1.7 million in 2008 prices) on behalf of Serpell’s committee.

Serpell’s Committee started work in May 1982 and presented its report, together with the minority report from Alfred Goldstein, to transport secretary David Howell on 20 December.

But the printed version was not published until 20 January 1983 and the intervening month was filled with media reports and leaks – for which BR was largely blamed.

Many of these focused on Option A and Goldstein’s breakaway report, in which he had said the ‘greatest area of opportunity is in altering the level of services and the size of the railway network’.

But there was huge opposition to more railway closures, both in lengthy debates in the Houses of Parliament and in a review by the Transport Select Committee.

Aftermath

When Margaret Thatcher called a general election in June 1983, Serpell’s report was shunted into a siding. After the Conservatives had been re-elected, David Howell was dropped from the Government.

Tom King was then made transport secretary, lasting just long enough to see Sir Peter Parker retire after seven years and two stints as BR chairman, and to appoint BR’s chief executive Sir Robert Reid (the first chairman of that name) as his successor.

Before the end of 1983 Nicholas Ridley, with whom Sir Robert Reid had a good working relationship, replaced Tom King.

By summer 1984, BR had gained government approval for East Coast electrification all the way to Edinburgh and the first of many approvals for new fleets of electric and diesel rolling stock, as well as Class 90 and 91 electric locomotives and Class 60 freight locomotives – a rolling stock renewal programme that was halted only in 1993 by John Major’s plans to privatise the railways.

In 1986 BR set up an organisation in partnership with the French and Belgian railways to plan services through a new Channel Tunnel.

So the Serpell report – and more importantly the reaction to it, much of it orchestrated by BR – became the turning point in the fortunes of the national rail network, which is now busier with passengers than it has been for 50 years.

Although there was always strong opposition to reducing the rail network, particularly since the Beeching cuts of the 1960s and ’70s, it actually shrank over 1,000 miles [1600km] following Serpell’s report. In 1981 total route mileage was 10,831 [17,431km], but this had shrunk to 9,826 [15,813km] by 2008. Almost half of the closures – 474 miles [763km] – have occurred since privatisation in the mid-nineties. The closures are almost entirely accounted for by freight-only routes.

A handful of passenger services have also been withdrawn since 1983, but some of these were associated with network improvements, such as when the North London Line was closed in 2006 between Stratford and North Woolwich, to be replaced by a new section of the Docklands Light Railway and the Abbey Wood branch of Crossrail (the Elizabeth Line). (Similarly, the Moorgate section of Thameslink was closed in 2009 so that the southbound platform at Farringdon Thameslink could be lengthened over the former Moorgate line junction to accommodate 12-car trains.)